This hidden gem of a Midwest city is often overlooked

The world’s greatest architect was dead, but nobody knew that this bedraggled man on The floor of the men’s room at Penn Station was the Louis Kahn. It was almost fifty years ago. Antonio Gaudí Because of his poor appearance, Kahn died after he was struck by an automobile tram. The delay in receiving medical attention that led to his death likely contributed to his death. Now, it would be two whole days after 73-year-old Kahn’s collapse on Sunday March 17, 1974 until his body–scarred, rough after nearly 24 hours of flying, and in rumpled clothes–would be properly identified in the morgue. When Kahn’s briefcase was opened, the sketches for Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island in New York City were found, a project that wouldn’t be completed until 2012. In fact, when Kahn died, the most recent work of his that he saw completed often went unmentioned in obituaries–a 660-seat performing arts center in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Fort Wayne is not the first to be overlooked. Most of us would be pressed to point on a map to this city of a quarter million people in northeast Indiana–even though so many of us have passed it taking the northern route on a cross-country road trip. But what those of us who so readily pass it by don’t know is that this city has a collection of works by some of the last century’s most important architects–Saarinen, Kahn, Wright, and Graves–plus a whole lot of history and charm. That’s why it’s the latest selection for our series on underrated destinations, It’s Still a Big World.

Fort Wayne has its own airport–a complex that looks like every other American midsize airport–but it’s also a mere three hours from Detroit, two from Indianapolis, and a couple from Chicago. For the long weekend, my home was The BradleyA historicist stuccoed building that covers an entire street block on Main Street. Fort Wayne, like many other American cities that were once industrial and mid-sized, is currently in transition. Much of that transition can be seen in the area around the hotel where a lot of the city’s recent and ongoing infill development can be found. The Landing is a mixed-use project that preserves some historic architecture and adds new apartments. Construction of the complex going into the former parking lot of the Aunt Millie’s Bakeries next door was in full swing.

If you find the race to capture and accommodate millennials and Gen Z urban planners fascinating, then take a walk or drive to Electric Works. This 39-acre, 18-building campus was once the heart of Fort Wayne, employing a third of the city’s workforce when it was a major General Electric manufacturing center. In the early 2010s, it was closed down as all other U.S. manufacturing centers were closing. Now, it’s being turned into a different sort of campus–open-floor plan offices, a food hall, chic industrial lofts, and so on–that the city hopes will give it a new center for social activity that reverses the sprawl and flight typical of the last half century.

The real architectural excitement started outside the city centre with an afternoon visit Concordia Theological Seminary. It is a modernist Nordic village built by Eero Svarinen in 1958. Saarinen was the architect of both the St. Louis Arch & TWA Terminal. This is what brought me to Fort Wayne. While researching for a story about his father’s immaculate house outside DetroitSaarinen is a place I was pleasantly surprised to discover. fils Although we were unable to visit the house, he had previously lived here in Fort Wayne. But then I saw he also designed this campus for the Lutheran church, and it’s nigh impossible to feel let down while walking around it. They’ve worked tirelessly to preserve Saarinen’s vision–even the dining hall’s original vinyl tile floors remain intact.

As you approach the campus, you will see a number of hut-like buildings that line the driveway. Their staggered pentagonal forms give a serrated edge and curve to the curving drive which mirrors the artificial lakes beyond. Geometry is at the center of Saarinen’s design here–rectangles, triangles, and, most importantly, diamonds. Bricks are placed on facades at an angle to look like diamonds. The side of the classroom building runs parallel to the main walkway. For those who are interested in small details like these: The acute angle for the diamond brick is the angle at which the earth spins on its own axis.

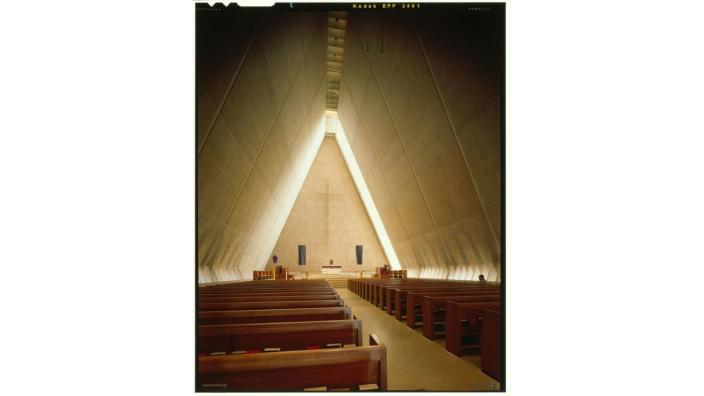

The pomp and circumstance is not something Lutherans embrace. sturm und drang of Catholic decor, they’ve still managed to pull off some drama with the centerpiece of the campus–its triangle-shaped chapel. It’s a place I wish one could experience from the inside out, to see and feel and hear what Saarinen has achieved inside, and then step outside and discover the little tricks he used.

The chapel’s interior is a lesson in minimalism and how it can inspire awe. Concrete panel walls with sloped inwards and upwards mirror concrete floors made of polished concrete. The backdrop for the altar is not the elaborate reredos you might find in other churches. Instead, it features more brickwork with diamond-paned windows and an oblong gold cross. Brickwork is lit by a golden light that shines through vertical slits at its roof. The brickwork is lit by natural light, which is not available at night. There are also small windows on the ground that provide soft illumination around the side aisles.

However, these windows are not visible outside. A border of smooth river stones adorns the concrete buttresses, as well as the Ludowici tile hanging eaves with extra ridges designed to look like wood stave churches. But if you peek under the eaves, there you’ll find the window slits, as Saarinen wanted the light bouncing off the river rocks and up through the glass to the chapel.

The campus remains almost exactly as Saarinen left. A small, but very welcome addition to the library gave students a view of the lake and allowed for more natural light. It is difficult to feel lost in time when you look around the classrooms and dining halls decorated with Siegfried reinhardt mosaics.

Concordia’s campus is on the northeastern outskirts of the city, but on the opposite southeastern side are two houses worth cruising by. The first is the John D. Haynes House, completed in 1952 as one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses–affordable houses designed for middle class families in his Prairie Style. It’s far from Wright’s most interesting or important, although, collectively, his Usonian houses are as important as anything else he did.

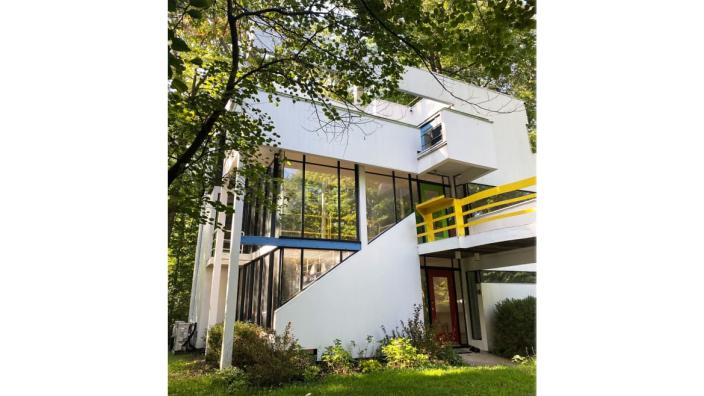

About ten minutes away, though, is the first commission of one of the last half-century’s more polarizing architects, Michael Graves. Graves, who died in 2015, was one the pioneers of Postmodern architecture. His most iconic buildings include the Denver Public Library, Portland Building, Louisville’s Humana tower, and the Walt Disney World Dolphin & Swan hotels. But in the ‘60s, Graves was just starting out and this home was built along a creek for friends of his. It looks like a Mondrian Cubist painting brought to life. Corbusier’s influence on Graves’ early designs is evident. Although it’s a little worse for the wear and the decor is, um, unique, it’s available for rent on AirBnB.

Louis Kahn’s death was marked by obituaries that spoke of his Salk Institute, Yale University Art Gallery and Exeter Library. They often forgot to mention the theater at Fort Wayne’s heart. (They also omitted Kahn’s two children from women who weren’t his wife. They were forced to sit out of her sight at the funeral. If Kahn had originally gotten what he proposed–multiple museums, a 2,500-seat symphony hall, theaters, gardens, and more–his Arts Center in little Fort Wayne would have rivaled Lincoln Center. Kahn instead gave us the Arts United Center with $2 million, rather than the $20 million required by all. This was his only commission in the Midwest, and his only performing arts center.

A staggering 120 buildings were demolished to make way for the compound. This was typical of the mid-20th-century. Kahn beat out the era’s other greats—Saarinen, Mies van der Roe, I.M. Pei—for the commission. It is a sphinx-like maroon brick building. Sphinx-like because while Miriam Morgan, the center’s chief operating officer who gave me a tour, insists there’s no evidence Kahn intended the entrance to the building to look like a face, only the willfully blind could fail to see it. Kahn might be as inscrutable as that. His most famous quote is: “‘What do you want, Brick?’ And Brick says to you, ‘I like an Arch.’”

If you do happen to stop in Fort Wayne, reach out on the theater’s website for a tour because Morgan is a font of knowledge and a lot of the fun of touring a work by somebody like Kahn are the little details.

Concrete here has a warm brown color that looks almost like molten stones. Kahn hated seeing ventilation, so there’s an open crack running along the bottom of the walls that works as a duct–good luck, I guess, if you lose something in there. The theater is a trapezoid set within a box–a violin within a violin, Morgan says, because a train runs behind it. Kahn also failed to include a way to move from the back of the house to the front without having to cross the stage or go outside. It’s always funny when touring works like this to learn what starchitects forget.

These marvels are examples of the architectural ideas that dominated the 20th Century. A building is found in the middle, which many modernists may naturally ignore. But it could be one of the most remarkable.

Charles Holloway’s mural Law and Order.

William O’Connor

As a work of American civic architecture, the Allen County Courthouse is almost unremarkable from outside. It is part a long American tradition of making small-town civic structures out of the great temples and palaces of Europe. A visual representation of American wealth and values–aping the Old World while also reducing their aristocratic aesthetic to less glamorous purposes. The facade of the limestone-marble Beaux-Arts façade is akin to many other libraries, courthouses and city halls. But once you step inside and through security, it’s one of the most wondrous spaces you’ll find in the U.S.

Close-up of the details in the Allen County Courthouse scagliola.

William O’Connor

Nearly every inch is covered in some sort of elaborate decoration, whether the dizzyingly patterned floors or the enchanting Art Nouveau frescoes by Paris Exposition Gold Medal-winner Charles Holloway underneath the building’s colored glass dome. Scagliola is a plaster that looks like inlaid marble. It decorates the walls of the entire palatial complex. To create the veins, a silk thread is dragged through the wall. This scagliola is actually the largest in America, covering 15,000 feet. The mind-blowing decor isn’t just in the hallways and atrium here–a series of courtrooms were decorated in what would seem to be an effort to outdo each other–visions in scagliola of pink, scarlet, blue, and dark green, each with their own colored glass dome.

One of the extravagant court rooms.

William O’Connor

My guide for the courthouse was Randy Harter, a local historian who walked me through the town and a general overview of the city’s history. The first gamechanger? The Wabash and Erie Canal made the town a major hub. Harter tells us that Johnny Appleseed died in Fort Wayne. The apple trees he planted were spitters and meant to be used for cider. Harter also had me pop into the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection at the city’s main public library. There are tens of thousands of documents related to Lincoln in the collection–newspaper clippings, letters, photographs, maps, and diaries–and there’s a rotating display of some of the highlights in a gallery in the library. Two particular items caught my attention. One was a photo of Mary Surratt, one of the Lincoln assassination conspirators. She was the first female to be executed in the United States and she remained innocent until her death. The second is Ghost of Abraham Lincoln photo, in which the former president’s ghost appears to be massaging Mary Todd. It’s the work of William Mumler, who used double exposure for his spirit photo hoaxes that engrossed audiences.

Mary Todd Lincoln, A. Lincoln’s Spirit 1872

Wiki Commons

Fort Wayne isn’t all about the past. I ate well, whether at the Banh Mi Pho Shop in a strip mall-like building on my way from the airport, local favorite Junk Ditch Brewing Company (don’t leave without ordering dessert), and Nawa. At nearly every meal, my hosts at Visit Fort Wayne made sure I was meeting citizens focused on the future of Fort Wayne–chefs, entrepreneurs, members of the LGBT community, and so on. Alex Hall, who manages Art This Way, a group that aims to create more public art in the city, gave me a tour. Along with local muralist Theoplis Smith III, Hall walked me around the city’s alleyways, parking lots, and little nooks where world-class muralists and graffiti artists have added color and a little pizzazz to formerly drab quarters.

Right around the corner from the hotel is the city’s newest public space, Promenade Park, which has water features (along with signs warning families there’s no lifeguard on duty and to refrain from entering if they’ve had diarrhea in the last two weeks), ping pong tables, kayak rentals, and a historic canal boat.

Before leaving town, I popped into the city’s art museum just to see what they might have going on. Fort Wayne is full of surprises. Vera Bradley, the founder of Fort Wayne, was also here. Also, this is where the first television set was created. But the most surprising is the town’s ability to claim legendary American fashion designer Bill Blass as its own. His childhood was marred by tragedy—his father killed himself—and Blass couldn’t wait to get out of town, leaving at just 17 years of age with all the money he could gather to New York City. But Blass would later in life say he was “just a Hoosier.” While he would still have needed to leave to become the designer he was, I think Blass would find Fort Wayne a much more interesting town now than the one he fled so many decades ago.

Get the Daily Beast’s biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast’s unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.