Dispatch from Bangalore, End of 2022 Edition

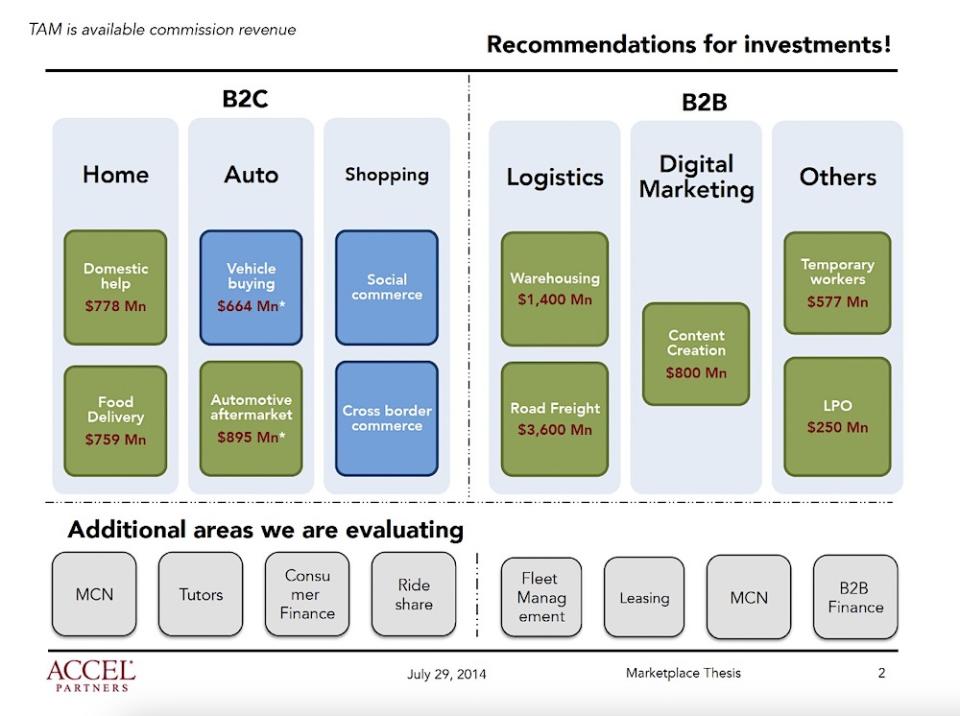

In 2014, Prayank Swaroop presented a pitch to Accel, a storied venture company, where he was an associate about India’s future market.

Snapdeal and Flipkart, India’s only ecommerce startup at that time, had shown some signs of scale. Swaroop argued that Indians will be more likely to go online for food delivery, warehousing and road freight, as well as other market areas such social commerce.

Swaroop, now a Partner at the Firm, was right. Urban Company, an organization that provides domestic help, is valued at more than $2 billion. Zomato and Swiggy deliver food to millions each month. Spinny and Cars24 sell hundreds, thousands, and each quarter, Spinny and Cars24 sell hundreds, thousands, of cars. DealShare, a social-commerce startup, is valued at nearly $2 billion, and Meesho at just under $5 billion.

Over 100 million Indians are now shopping online each month. This is in addition to the hundreds of millions that have migrated online over the past decade. India has seen its unicorn pool double to more than 100 over the past two decades. In the last five years, it has received investments of over $75 billion from tech giants Google and Amazon, as well as venture funds Sequoia and Tiger Global, SoftBank and Alpha Wave, Lightspeed, and Accel.

Swaroop’s presentation, 2014. (Image credits: Accel)

But as the local startup ecosystem closes one of its toughest years, it’s now staring at another question that it has long been able to brush off as benign: exits.

Half a dozen Indian startup companies in consumer tech have gone public over the past year. None of these startups are doing well on the local stock markets. Paytm is down 60%, Zomato 58% and Nykaa 56% respectively, Policy Bazaar 52% and Delhivery 38%.

This is despite the Indian stocks outperforming the S&P 500 Index and China’s CSI 300 this year. India’s Sensex — the local stock benchmark — remains up 3.4% this year, compared to fall of 19.75% in S&P 500 and 21% in China’s CSI 300.

Many Indian startups, including Snapdeal and MobiKwik, have postponed their plans to list as the market changed direction. According to two sources familiar with the matter, Oyo, which had planned to list in January next, is unlikely that they will go ahead with their plan.

Flipkart, valued at $37.6 billion and majority owned by Walmart, doesn’t plan to list until at least 2024, according to a person familiar with the matter. Byju’s, India’s most valuable startup, doesn’t plan to list in 2023 and is instead moving ahead with a plan to list one of its subsidiaries, Aakash, next year, TechCrunch previously reported.

According to sources familiar with the matter, those looking to move forward with plans to go public will encounter another obstacle: Several global funds, including Invesco which finance the preIPO rounds, are pulling out of India’s market following a shaming in China and other emerging markets.

Long-standing concerns have been voiced by LPs about India’s inability to deliver exits. The industry’s early attempts to do so in the last two years are nothing to be proud of.

Indian venture funds tend to get the majority of exits via mergers or acquisitions. However, even these exits are becoming more difficult to find.

One of India’s top venture funds stated that VCs who backed SaaS startups in the early stages at a valuation below $25 million had a better chance of exiting. As we’ve seen, SaaS investors are unable to make a profit when the startup’s exit value is below $25 million.

II

On a recent evening at a private gathering of a few dozen industry figures at a five star hotel in Bengaluru, many investors were exchanging notes about the deals they had been evaluating. Partner complained that the quality and quantity of pitches have declined, even though they were getting more.

People familiar with the matter say that two prominent venture funds, which run cohort programmes or accelerators of early stage investments, are having difficulty finding enough qualified candidates for their next batch.

I will argue that it’s not just that the quality of startups that are emerging has taken a hit, it’s also investors’ appetite and mental models for what they think may work in the future.

Crypto is one example. Most Indian investors did not make it in time to invest in the web3 space. (You won’t find many Indian names on the exchanges CoinSwitch Kuber or CoinDCX. I was recently pointed out by Polygon, a prominent VC at the largest crypto VC funds in the world.

Many Indian companies that employed a lot of crypto analysts last year have been forced to resign and ask their staff to shift to other areas.

Fintech is another area of concern to investors. India’s central bank this year pushed a series of stringent changes Learn more about how fintechs lend money to borrowers The Reserve Bank of India has also been growing in importance scrutinizing who gets the license To operate non-banking financial businesses in the country in moves which have sent a shockwave to investorsThey are now extremely concerned about how much conviction they have and the level of underwriting confidence they have for the sector.

Venture investors are increasingly looking for opportunities to invest in banks. Quona and Accel recently supported Shivalik Small Finance Bank. Many are deliberating an investment in SMB Bank India, one of the banks that has aggressively partnered with fintechs in the South Asian market, TechCrunch reported earlier this month.

Investors’ enthusiasm in the edtech market has also cooled off after re-opening of schools toppled the giants Byju’s, Unacademy and Vedantu.

According to Tracxn, Indian startups raised $24.7billion this year, a drop of $37billion from last year. Due to market dynamics and the funding crunch, startups had to fire as many as 22,000 employees in this year’s fiscal year.

Over a dozen investors I spoke with believe that the funding crunch won’t go away until at least Q3 of next year even as most investors chasing India are sitting on record amounts of dry powder.

As we approach the new year, investors will be questioning their convictions. Many believe that there will be several down rounds of major startups. Meesho refused to raise money at a lower valuation this year. Two people familiar with the matter claim that PharmEasy valued at $5.6billion was offered new capital at less than $3 billion this year. (PharmEasy has not responded to a request for comment.

“2022 began strongly and it appeared for a while the Indian venture financing market would be subjected to different gravitational factors than U.S., China, which were experiencing dramatic declines. But this was not to be. Blume Ventures investor Sajith Pa said that eventually, the Indian market faced the same macro headwinds than the U.S. or China venture market.

Pai said that growth-stage deals accounted for the majority of funding last year and saw anywhere from a 40-50% drop this year. “The decline was primarily due to growth funds stopping investments, because multiples in private markets were more expensive than their public peers and weak unit economics for growth stage companies.”